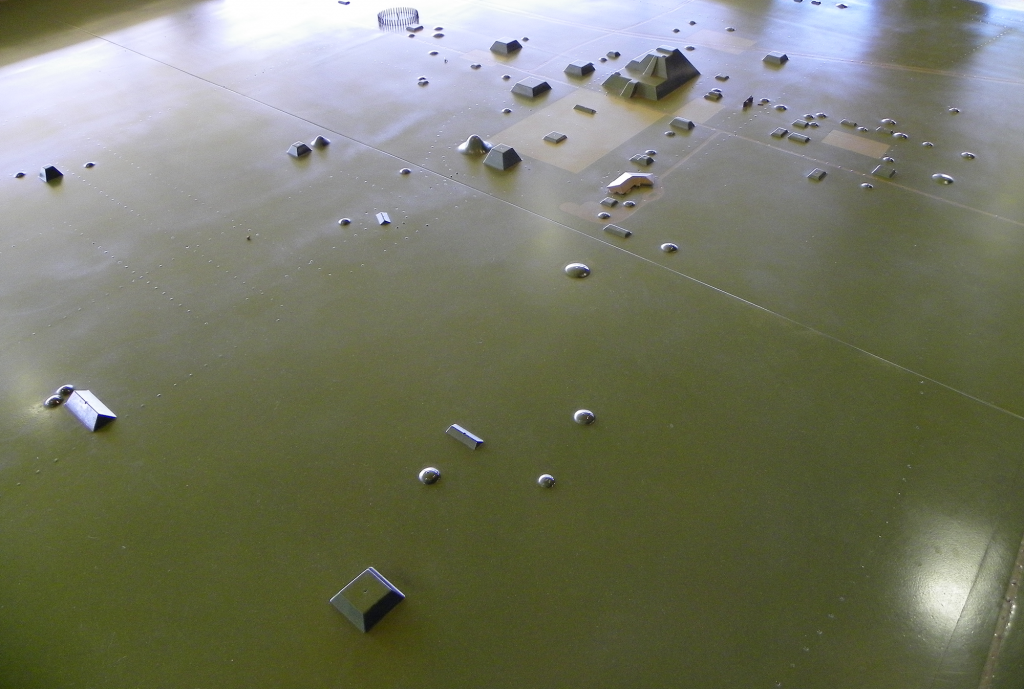

Map of Cahokia mound complex from National Geographic.

Cahokia Mound settlement sits 9 miles to the northeast of St. Louis, MO (6 miles to the northeast of East St. Louis, IL). While the area was settled in the 7th century CE, mound construction started about 200 years later. This complex of 120 mounds (now 80) sits in the fertile floodplains of the mighty Mississippi in a territory known as the American Bottom. In this context, Cahokia’s largest mound, Monk’s Mound, is surpassed in height and volume only by the Milam Landfill (also known as Mount Trashmore) in East St. Louis. Only sometime in the last 40 years did this trash heap overtake Monk’s Mound. Was there a ribbon cutting ceremony when this 20th century trash-made mound finally overtook the man-made 9th century one? Given the slow demolition of East St. Louis since the 1960s, we might wonder what material percentage of the modern city was sacrificed to achieve the title of tallest mound in the American Bottom. Could Milam Landfill now be christened Top of the Bottom?

Just as Cahokia was being settled, 300 years or so before Monk’s Mound was built, other mounds such as those at Crystal River, FL were built of oyster shells. These forms seem intentionally built to serve as temple platforms, but perhaps more interesting were those nearby made of waste (middens) which slowly, maybe unwittingly, came to define different zones within the complex: a prehistoric form of trash urbanism.

Of course the Romans had their own mountain of trash, Monte Testaccio. What started around 50 CE as a storage heap for discarded amphorae used to ship oil across the sea grew into a hulking ceramic mountain. The material properties of this mounded, fired earth would later be rediscovered when wine caves were excavated into the bottom of the hill, tapping its cool constant temperature for distribution to the drinking establishments that would ring its perimeter.

Caught somewhere between archaeology, geology, and scatology, these mounds pose an earthy challenge to how we live with, on, or in, the past.

For more on Monte Testaccio and what it offers for contemporary landfills, see Michael Ezban’s “The Trash Heap of History.” For more on the agency of the past contained in such living heaps see Jennifer Scappettone’s “Garbage Arcadia: Digging for Choruses in Fresh Kills,” in Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale.

Satisfying a bonus obsession, an exquisite visitor’s center site model of the Cahokia Mounds transforms the amorphous ambiguity of earthen form into crisply rendered bronze geometry: