What’s the easiest way to make a mountain out of a mole-hill? Just keep heaping. Probably the easiest way to make “architecture,” mounding dates back millennia. While Laugier’s Primitive Hut assembles elements from the landscape into architecture, the mound operates simultaneously as architecture and landscape. Unlike other protoarchitectural expressions, mounding – the manipulation of the earth – always seems to connect to the hidden. There is always more than meets the eye in the mound. Prehistoric middens often reveal more information about past societies and ecologies than written documentation. Tombs, sarcophagi, secret passageways, treasure, the unknown…

In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Roy Neary (played by Richard Dreyfuss) becomes obsessed by a particular unknown form (later understood to be Devil’s Tower, Wyoming, the location of alien contact). Although the profile of this form is striking, it is its massive materiality that is the touchstone for Neary’s obsessive behavior. Instead of simply drawing the stark silhouette of the tower, he sculpts its likeness out of the materials of his every day life: first sculpted dollop of shaving cream, then a mashed potato mound at dinner, and finally, in a coup de grâce, a living room effigy of repurposed bricks and uprooted shrubbery from his lawn and, of course, dirt.

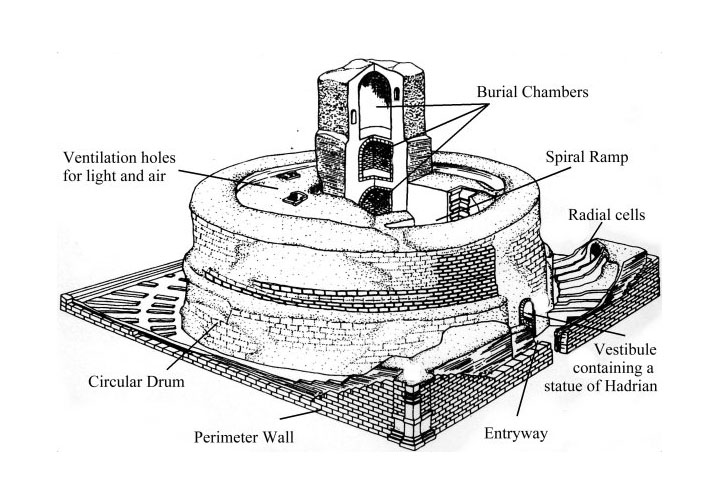

Neary’s mounds, and Devil’s Tower itself, seem just a step away from the mound contained inside Hadrian’s Mausoleum in Rome, whose plan reveals an extreme relationship between habitable space and solid rock/rubble (for more on the prominence of poché in Rome, see this article in FLOOR).

Axonometric view of Hadrian’s Mausoleum (now Castel Sant Angelo) in Rome demonstrating mounded earth encased by brick.

David Gissen’s proposal for the reconstruction of the Mound of Vendôme (2012). Here the mound indexes the destruction of the Column of Vendôme in Paris, itself a reconstruction of Trajan’s Column in Rome.

Many recent Radical Craft projects follow this obsession, in part in reaction to architecture’s recent indulgence in the lightweight and superficial. Soms Atoll oscillates between assembled architecture and sculpted landform. Trajan’s Hollow examines the poché (both material and programmatic) of monumental mass. Even Inversion Sky attempts to recreate the thickness and mass out of the thin and airy.